I’m currently working on a prototype for a project and needed a super flexible and reusable event system. I took some inspiration from Far Cry’s dynamic, emergent systems and made this… thing (GIF at 1/4 speed):

I also took a lot of inspiration from this wonderful GMTK video:

Breakdown

So what the heck is happening here?

Well, right now I call them “pings”, but they are definitely worthy of a more descriptive name in the future. They act as a “multi-dimensional event system” for games. They aren’t 4D in the way that you’re probably thinking, however. The basic gist is:

- A ping is fired off in code and added to an internal list to be regularly “pulsed”.

- Every “pulse”, all ping listeners within range of the ping that can respond are notified.

- Each valid responder will receive a notification every pulse unless it returns a response, after which it will no longer be considered as a responder for that specific ping.

So, how are these useful? In so many ways I never even realized until I implemented this system. Here’s a few examples of the types of problems this solves in my current project:

- AI senses. This works for sight, hearing, heck, even smell. For example, the player’s feet can create pings for each step.

- Reduces coupling. Pings can have any amount of data associated with them, and can thus track the “source” of the ping. I use this to, for example, have the player create a “wants reload” ping with a very small radius. The player’s gun will pick up this ping and trigger the reload. Using this model, the player doesn’t need a reference to the gun. The gun’s resulting “reload” ping can be then picked up by nearby enemies, as if they are “hearing” the reload and know to fire on the now vulnerable player. It’s also picked up by the UI, which can show a reload animation in the HUD.

- Extremely easy to write debug tools for. The above GIF shows how much information can be very easily visually parsed by rendering debug gizmos.

It should be noted that this system separates the concerns of “listening” and “responding” – they are two separate interfaces. This is because a single listener might be able to hear multiple different types of pings.

Now with all of that out of the way, time to dive deeper into the individual elements of the equation: pings, listeners, and responders.

Pings

Ping is an abstract class that you create a derived class from, such as TakingCoverPing, or ReloadingWeaponPing. They are basically like regular code driven events, except with 5 distinctive differences. Pings by default are:

- Positional: They have a 3D position in the world.

- Radial: They are spherical in shape and have a radius.

- Temporal: They have a start time and duration.

- Continual: They don’t have to just be fired once. Instead they “pulse” at a regular, custom interval (if desired).

- Global: Responders don’t register to specific instances of these pings. I’ll get into this more later.

There are some hidden bonuses that can be derived from the above properties. For example, since pings are positional and radial you can calculate a signal attenuation value for any 3D position. When used with AI senses this attenuation value can then be fed into RNG systems to determine if an enemy “heard” a sound that they were a bit far away from.

The continual nature of these events isn’t a very widely applicable property, but does allow for very slick implementations of specific behaviors. A good example can be found in the Hitman games (specifically the trilogy started in 2016). Any weapon not in an expected location will attract the attention of NPCs. Instead of engineering a specific AI sense to accomplish this, weapons that are dropped outside of specific locations could create a ping with an infinite duration and regular pulse rate. While you still would need to write the response behavior, you don’t need specific code to have the AI pick up on these sort of gameplay conditions.

By default Pings can also store the source GameObject that fired the ping. This is used by the debug visualizers to draw a line from the ping to the object that created it. It’s also used by many of the responders to determine if specific pings are relevant to them. Going back to the gun reloading example, each gun only responds to a WantsReloadPing if the source of the ping is in their transform hierarchy (in this case it’s the character that wants the reload).

Listening

Listeners inherit from the IPingListener interface, which just describes the listener’s Position and Radius.

Yep, just like pings, listeners are also positional and radial in nature. This means that determining which listeners can “hear” a ping is done via a very simple sphere overlap check.

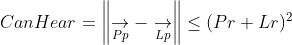

Where L is listener, P is ping, p is position and r is radius:

This is a very important distinction between pings and other event systems. In a typical Observer-pattern-like event system, each handler registers itself to specific instances of events. It will always receive a callback for those instances of those events as long as it remains registered.

A typical event bus implementation will remove the coupling between the owner (publisher) of the event and the handler (subscriber). Instead, anything can fire an event of any type via the event bus, which then selects handlers based on the type of event. This is also known as the Mediator pattern.

Pings are closer to an event bus in nature. However, with regards to selecting handlers in this system, I refer to this process as “Listener Discovery” due to how varying the resulting list of handlers can be based on game state.

Some of the information derived during listener discovery is stored in a struct called PingLocality and passed to the responder. It stores the square distance from the listener to the ping, as well as the attenuation of the ping based on the listener’s position.

Its very easy to abuse listener setup to achieve more flexible behavior. For example, a global listener just needs a radius of float.PositiveInfinity (this is how the UI listens to events in the world). Listeners can be attached to transforms by returning transform.position as the Listener’s Position property.

Responding

The inheritor of IPingListener will also need to inherit at least once from IPingResponder<T> in order to do anything beyond “hear” an event. This interface looks like this:

public interface IPingResponder<in T> where T : Ping

{

void RespondToPing(T ping,

in PingLocality locality,

ref PingResponse response);

}

The first two arguments have been discussed, but the last needs explanation. As I previously mentioned, whether or not a listener will continue to receive notifications about a nearby ping is related to the response given. PingResponse is an enum with 3 values:

- None: This responder needs further notifications for future pulses for this ping.

- Acknowledge: The responder no longer needs to know about this ping.

- SoftAcknowledge: A very specific response, I’ll explain in a bit.

When the system receives a “none” response, it’ll make sure to notify that responder again during the ping’s next pulse. If it receives a “acknowledge” response, it’ll log some information about the acknowledgement, and add that responder to the ping’s list of acknowledgers to ensure that it’s ignored during future pulses. A “soft acknowledge” is like a “none” response, except it is logged in the same way as an “acknowledge” response. Again, this is very specific and is only used for cases where you want to know that the ping was potentially relevant to a receiver.

As a reminder, the primary reason why listening and responding are treated as separate concerns is so classes can inherit multiple times from IPingResponder<T> with different types for T. This allows a single object to respond to multiple different types of pings without having to specify unique listener position and radius values for each response.

Wrap Up

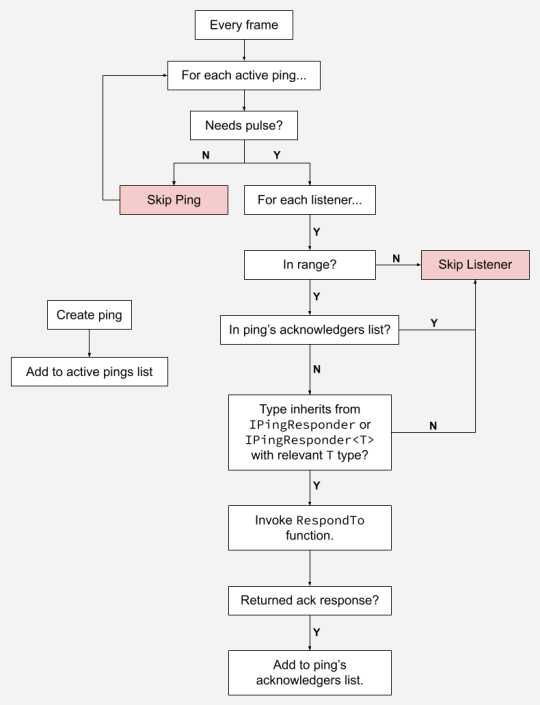

Everything above can be summarized into this potentially overwhelming flow chart:

That’s about it! There’s some other details not really worth mentioning, such as using object pooling for Ping subclass instances, or potential future optimizations on listener discovery (i.e. using an octree). I also plan on writing a “history visualizer” to show historical ping information. This is important due to how transitory these pings can get.

I’m curious to know what people think about this sort of system. If you want to chat about it, here’s where you can find me.